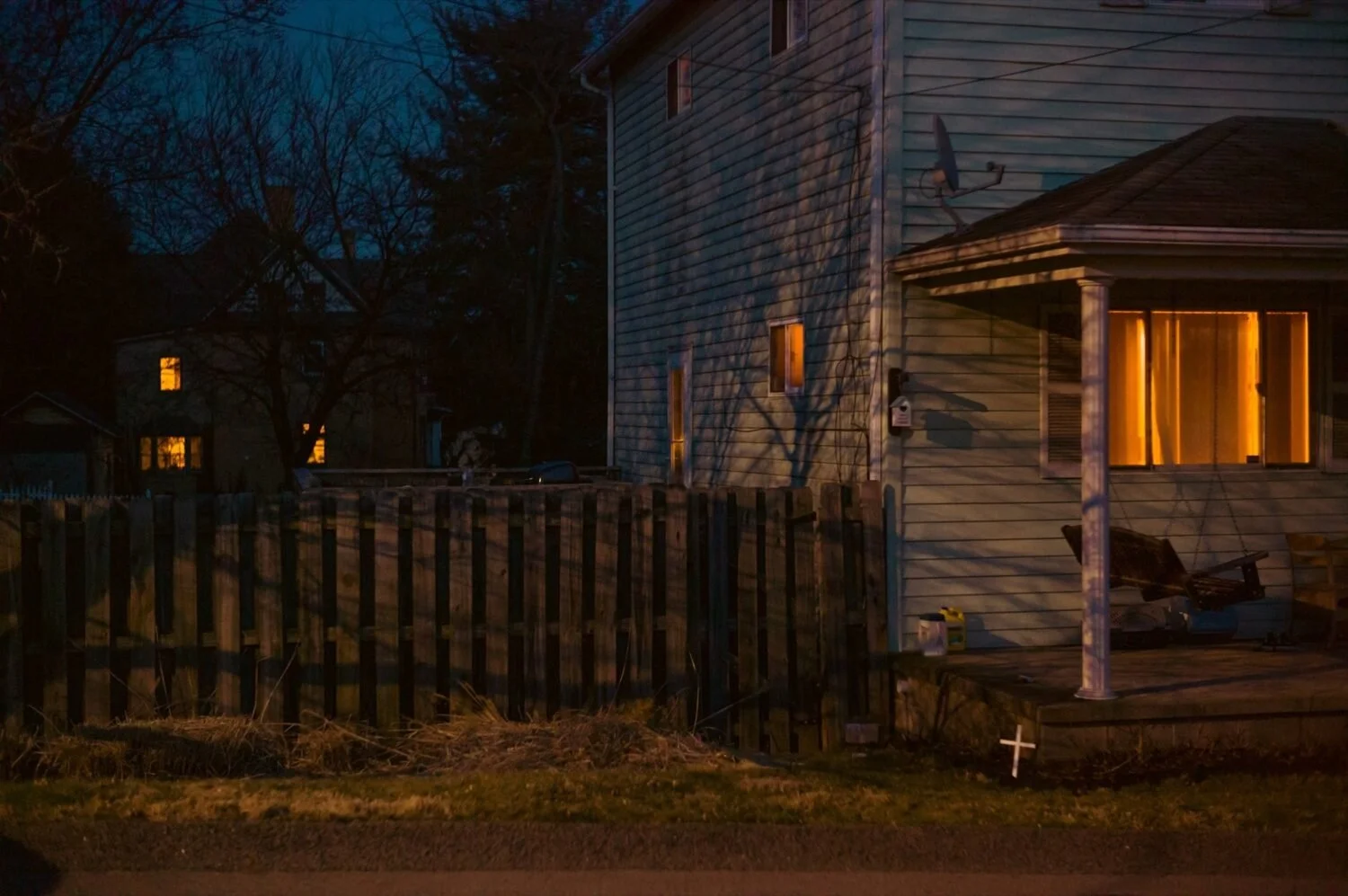

Untitled 20, Life On Mars, 2022

John Barbiaux is a self-taught photographer from the greater Pittsburgh area who works across a breadth of genres ranging from landscape and street photography to composite images. His work evokes strong emotions and transports viewers into whatever world he finds himself photographing in, whether that be calm rolling landscapes at sunset or bustling energetic cities. Silver Eye Scholar Will Litchholt writes:

“I was first introduced to Barbiaux through his series Life on Mars. Born out of the pandemic, Life on Mars uses the suburbs to depict an alternate reality devoid of humans where houses and trees become the living inhabitants of these serene suburban environments. Growing up in the suburbs just outside of the buzzing New York City, I have always been intrigued by the dichotomy of city and suburban lifestyles. After moving to the more urban part of Pittsburgh for college, this dichotomy became even more important to my own identity and my artwork.

Barbiaux’s expansive body of work showcases the hectic feelings of city life juxtaposed with serene suburban landscapes which speaks to me and many others from my hometown that split their early years between suburban NJ and New York City. Barbiaux employs the use of moody natural lighting, vintage lenses, and minimal gear to create captivating images of the suburbs he grew up around, making viewers feel a sense of inhabited comfort while still being outsiders.

I further resonate with how Barbiaux uses photography to learn about himself and unpack past memories. Art can be its most beautiful when it is an expression of the artist creating it and Barbiaux’s lenswork is truly an authentic and captivating representation of himself.”

The following interview contains edited highlights from a recent conversation with the artist.

Will Litchholt: John, the first question I had was just for a little background of how you first got into photography and where you are now?

John Barbiaux: I have loved the idea of photography since I was a kid. I can remember getting little disposable cameras and literally just burning through the film within like 5 seconds just because I loved the tactile feeling of pressing the shutter and then cranking it. I mean, even to this day, I still shoot film and that’s still probably my favorite part of it, you know?

But I'd say seriously, it was like 2008 [that I got into photography]. The recession had hit and my other business is finance so stress was through the roof… I was searching for something to get me out of that stressful world.

…I started with landscape photography and then I started to do some research and look into folks I had admired, you know, people like Alex Webb…. That got me excited about it because now there's this other facet of photography that I could explore here at home, right? I don't know if you've experienced this yet, but I think there’s a rite of passage for photographers as they go through their career and at first it's like, well, we've got to travel hours away to find interesting things to photograph, because everything around here is just boring, right? And honestly, even within the last four years I realize how naive I was to think that because now I'm seeing beauty literally everywhere.

WL: I was really interested in your series Life On Mars, especially how it contrasts with your greater body of work which consists of fractal constructed cityscapes with intense energy and color. You mentioned on your website that you shoot Life on Mars more organically and spontaneously, and I was kind of curious about this transition in creating more empty-feeling scenes that are reflex-driven images of the suburb.

JB: What brought me here to Life On Mars was when COVID hit. At that time, I was working on a project that I was doing in Pittsburgh, Boston, Philadelphia, and DC. It was just street photography with the idea that a lot of those images could be used to create the fractal cityscapes.

Life on Mars has been a very personal project and it’s just now it's getting a ton of traction... So that's really cool because here's something that feels like I birthed, and it has a life.

So when 2020 hit, I actually canceled every one of my commissions I had… My mental state was dwindling because I had started doing this [earlier work] as an outlet, and now … there’s so much pressure, you know?

Asking myself that, it's like, well, I don't know what my thing is anymore because I've been doing stuff for other people for so long. What am I capable of? I didn't have any idea of that over the last 10 or 15 years; had I improved or was I just doing the same thing?

This whole project was created as me trying to figure out who I was as an artist. What am I able to do? What creative vision do I have? I'm as surprised as anybody where it ended honestly, so that's been an interesting endeavor…

WL: So you touched on growing up around these areas that I did too. I grew up in the suburbs of New Jersey a little bit outside of New York City and I think I get a big sense of nostalgia from all the images in Life on Mars. I was wondering if you felt that for you, the dialogue between life in the suburbs or even just more rural areas and the city has been something important to you, especially since you've traveled around the country.

JB: I think one of the big shifts I made in my mind was that in the city with people and the chaos you could stand in one spot and things will line up eventually and then you could photograph it. But in the country because that's not happening it’s like everything's static. But what's amazing is you can make it happen by just walking because as you're walking, the perspective is constantly changing. Houses are shifting, trees are moving, and so your subjects are all lining up in these really cool ways. The goal was that I wanted to walk and then as soon as that happens, I want to get my camera and take that photo without thinking about it.

…Now I'll actually stop after I've taken the photo and I'll look around to try to figure out what it was that caught my eye. And [when editing] I'm noticing there's a disconnect between–and I don’t know if this is true for everybody–our subconscious and our conscious. And not to get too far into the weeds here, but [Sigmund] Freud talked a lot about that and how your dreams were your subconscious’ ability to talk to your conscious. … Like what's actually going on in your inner mind? What is it saying to me? …As I'm doing this stuff I'm trying to learn as much as everybody else is.

So for me, as I was doing this project in 2020, at first I was sensitive about the fact there weren't a lot of people. It was very different street photography and I'm like, well, do these images have the credence or the impact that other stuff did? But then I realized very quickly that what I'm photographing is more real than anything I ever saw in a city. For example; somebody's backyard… They're not putting different outfits on it every day to show the personality they want to show or to be who they want to be. That's just them. That yard is their reality, and what a privilege it is for me to be able to visit and photograph those areas and people are very receptive for the most part.

…But I do think it's important to note that I am still so careful. I will not go in somebody's yard and I won't even go in their driveway. I am always on a sidewalk or someplace public, mainly because I want to respect them, but also because I respect the craft…

Empathy is huge, right? If you're a street photographer and you don't have empathy, I don't know how you do it.

WL: I was curious as to how a lot of the images in Life on Mars are taken at dusk, which could be a romantic and nostalgic lighting, but also it could also be ominous because it's right before dark. I was wondering why you feel you resonate with this transitional time between day and night?

JB: Oh my goodness. I mean I can give you 800 analogies of why that's such an important time. I'll give you the basic answer, which is a lot based on availability, like when I can do it. I've got two different businesses, a family with kids, a wife, aging parents, you know, all that good stuff. So often it's the only time I can photograph, but I will tell you I don't shy away from shooting in the afternoon, I love harsh light too.

I also realized that at that time of the day, whether it's the morning or the evening, you’re introducing more dynamic lighting into the scene, which creates such a more interesting photo. So everything that Gregory Crewdson is doing is he's trying to emulate reality instead of just going out to find it.

…I don't know if that's an answer for you or not but of course it's truly just that it's the best light. I mean you've got so many different options and you can find whatever you want. If I don't like this one light I can walk a block and I’ve got a different light.

Most photographers are like, “Ohh golden hour.” I’ve got 15 minutes and I’ve got to hustle. But if you're not worried about when the sun's gone down, now you've got all this other dynamic light and you can keep shooting. It is so liberating to realize I can stay out here all night.

WL: So diving deeper, on your website you had mentioned the idea in the series of being an inhabitant and an outsider. From the images I get a bit of a sense of being an outsider as in a lot of the images we’re sort of peering around corners or over fences to view these houses. Could you maybe talk a little more about that sort of duality there?

JB: Yeah I mean it's interesting because there’s something in this series that I didn't realize initially. When you take a photograph of somebody's house–the side of their house, the back of their house–there's always a window. The windows are almost like eyes looking back at you because you have no idea what's behind them.… As I was creating these images it was interesting because as I'm editing and looking at them, I feel like I'm not supposed to be here. You know, like I'm not supposed to be looking at this. There is definitely this juxtaposition between those feelings.

But you know, as far as the being on the outside–and I don't know, maybe that's why I do photography or maybe it's because I do photography–I feel that way… I tend to feel like I am in the margins all the time, like I'm seeing what's going on but I’m not an active participant if that makes sense. I think that lends itself well to being a photographer, [an outsider feeling] is not super depressing if you're already used to it.

I guess I can make an argument for wanting to get involved with your subjects and learn about them. Certainly if that's what you're after then you should do it, but I also could make an argument for just being a fly on the wall. Let somebody exist and that's what I am most curious about.

…I'm one of the people that think that there's more good in this world than bad. People have a lot to offer each other but we do live in a world now where, with social media and politics, it doesn't behoove them to have us feel that way. It’s like we should all be at each other's throat all the time because that's what generates the most revenue for those people. It’s so frustrating.

So, yeah, I guess there's a part of me that feels like I'm on the outside looking in. That's what I feel like and I'm trying to learn. I wanna learn about you, like what makes you guys tick? Like why am I really that different, you know?

I'm fairly sure most people have those same questions too.

Participating Artist

For over two decades, John Barbiaux has developed an extensive body of work dipping into the worlds of street, landscape, and travel photography. A self-taught photographer, Barbiaux has explored his medium through analog, digital, and composite images, capturing a breadth of subjects from sweeping cityscapes and natural vistas to the streets of small American towns. The progression of his portfolio and his life has come with an affinity for framing quiet yet poignant moments amongst everyday backdrops. Barbiaux’s photographs have been published in the likes of National Geographic Travelermagazine among other publications.